What is a virtual field trip?

Introduction

The term ‘virtual field trip’ means different things to different people. In this project, we restrict the term to those approaches that seek to replicate the familiar ground-level perspective of being in the field.

At its core, a virtual field trip can be defined as a digital resource that allows a user to visualise and interrogate a remote location using imagery and other materials as appropriate (e.g., data, maps, journal articles) (Hurst, 1998; Woerner, 1999; Stainfield et al., 2000; Klemm and Tuthill, 2003).

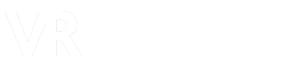

Technology is central to the virtual field trip concept because it plays a pivotal role in determining what can and cannot be achieved in these virtual environments. Perceptions of what constitutes a virtual field trip will therefore change over time in line with technological advances.

Over the last two decades, technological progress has enabled virtual field trips to transition from simple web pages to a range of more sophisticated approaches, including those based on virtual reality which seek to provide users with an immersive, simulated field experience (e.g., McDougall, 2019).

Although this variety provides educators with much-needed flexibility, a consequence is that the term ‘virtual field trip’ now means different things to different people.

The technology used for virtual field trips has changed – or perhaps become more varied – over time.

Table of Contents

In this project, we restrict the term ‘virtual field trip’ to those approaches that seek to replicate the familiar ground-level perspective of being in the field.

Immersive and non-immersive virtual field trips

A useful distinction can be drawn between immersive and non-immersive virtual field trips because each type presents different opportunities and challenges. A useful distinction can be drawn between immersive and non-immersive virtual field trips because each type presents different opportunities and challenges.

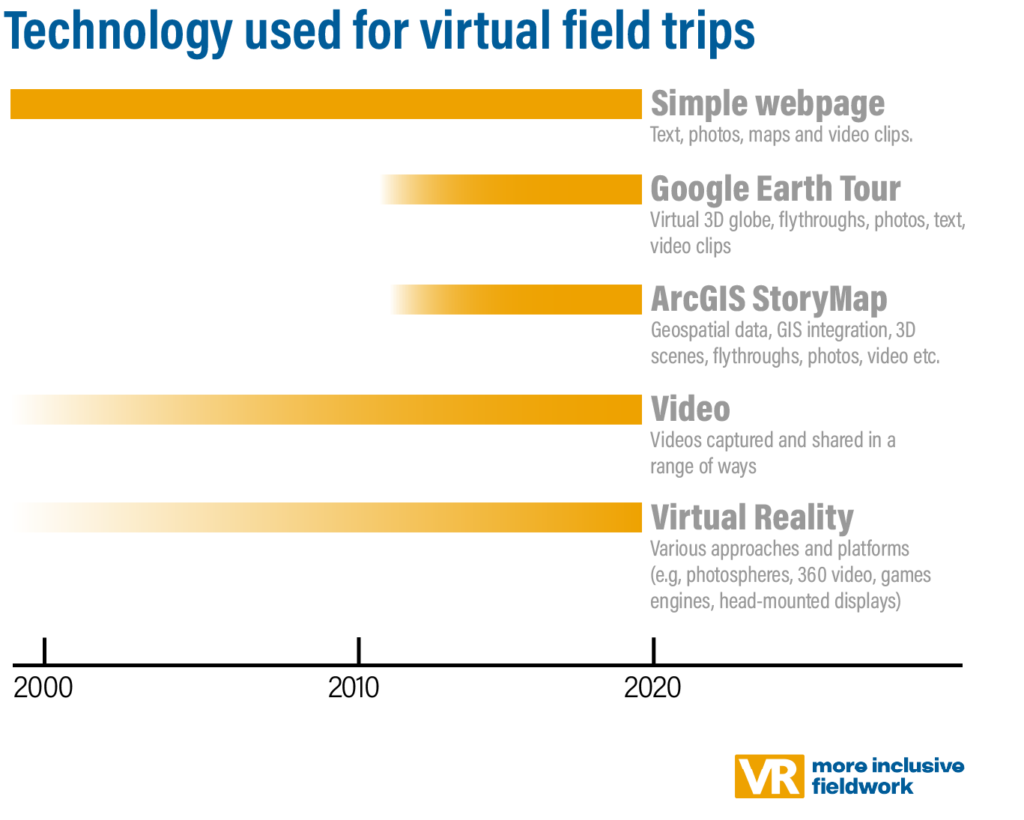

In an immersive virtual field trip, you are surrounded by the environment. Google Street View is an example of this because of its 360° imagery, which allows you to look all around.

The term virtual reality (VR) can be used to describe immersive virtual field trips. Google Street View is an example of photography-based VR.

Google Street View is an example of immersive VR because you are able to look all around. Viewing this example in full-screen mode on a large monitor will result in a more immersive experience than viewing it on a laptop.

Virtual field trips can be created using existing Google Street View imagery such as this one, or you could upload your own photos to this service. There are pros and cons to this approach, as discussed elsewhere on this site.

Non-immersive virtual field trips are primarily collections of location-specific resources (e.g., photos, videos, maps), which can be presented in many ways. Popular platforms for developing these currently include Google Earth Tours and ArcGIS Story Maps. Although these (and other) approaches may be visually rich, the absence of ground-level virtual reality at their core means there is less immersion and autonomy for the user. However, it is possible to embed ground-level virtual reality in these resources, which blurs the distinction between immersive and non-immersive techniques.

Non-immersive virtual field trips are collections of photos, videos, maps etc. They may include an element of VR (360° imagery), but this is not central to the approach.

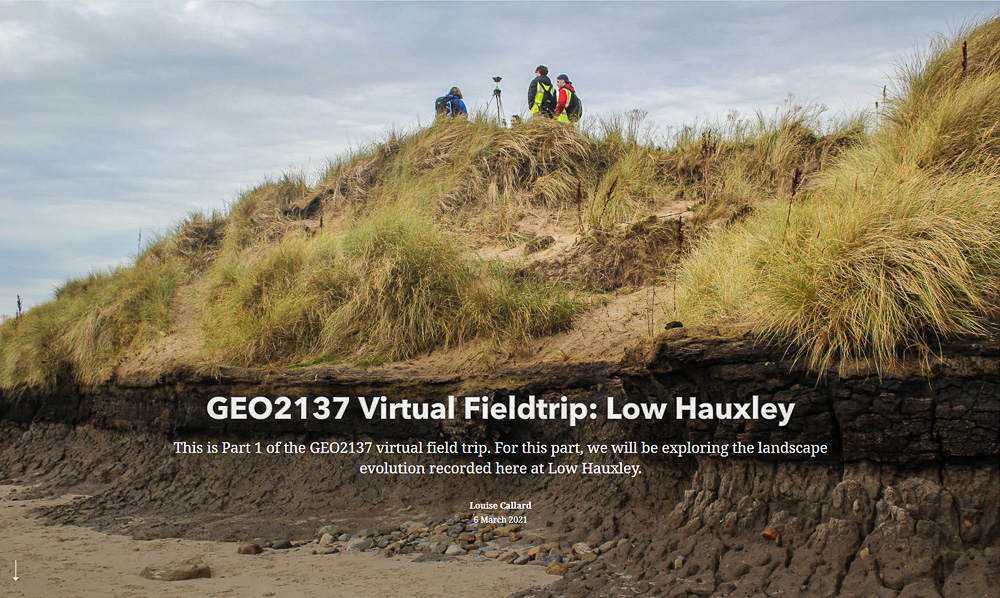

This excellent ArcGIS StoryMap was developed by Dr Louise Callard and Prof Andy Russell (Newcastle). It is based around a series of videos and student activities, with an introductory section comprising an interactive map and an embedded Google Street View.

Virtual field trips: guided or self-guided?

Some virtual field trips are self-contained, information-rich learning ‘packages’ (guided) whereas others are provided without any guidance (self-guided). There are pros and cons to both approaches.

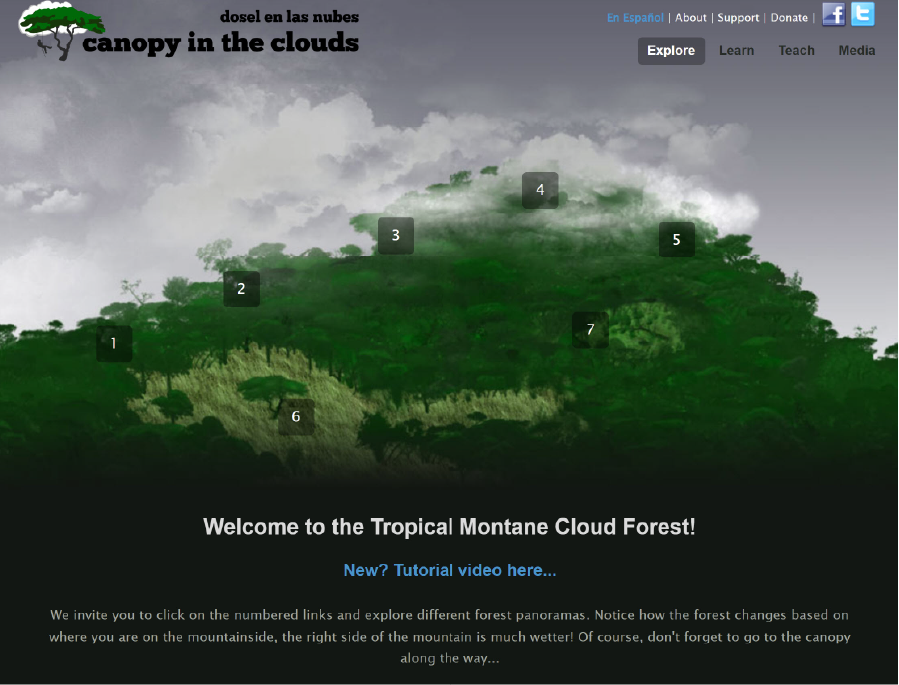

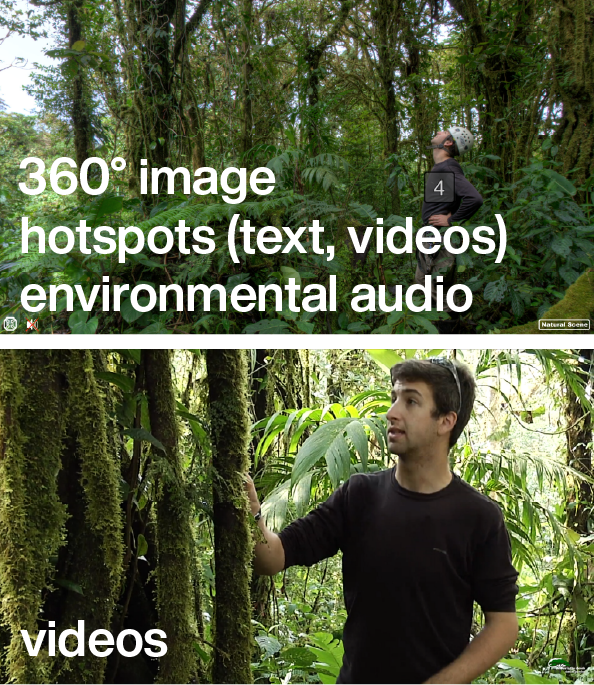

Canopy in the Clouds is an example of a guided (i.e., information-rich), immersive virtual field trip. It comprises seven sites within a tropical montane cloud forest. At each site, 360° imagery and environmental audio provide an immersive experience. Information (guidance) is delivered via videos embedded in the 360° imagery. It is possible to visit sites in any order, although here they are numbered to highlight the recommended route.

A GUIDED virtual field trip includes enough embedded academic content to make it a standalone resource. In other words, it can be used without additional instructor input.

Canopy in the Clouds is a guided virtual field trip. It is based around 7 photospheres, one for each site. Within each photosphere are clickable hotspots providing the viewer with information in the form of text, photos and video clips. Information about cloud forests and the study area is provided elsewhere on the website.

This is a high-quality resource, and all the more impressive given it was first launched in 2010. It appears to have been developed for outreach purposes.

Alternatively, virtual field trips can be self-guided. The absence of embedded academic content means these ‘bare bones’ virtual field trips are not standalone academic resources. Instead, they need to be placed within a teaching unit that provides students with the necessary background knowledge and skills. Student learning activities (e.g., worksheets) also need to be designed for these self-guided virtual field trips. This approach is exemplified by most of the virtual field trips provided by Stanford Earth Sciences (where they are referred to as ‘virtual field sites’) and Geography at the University of Worcester.

A key benefit of self-guided (‘bare bones’) virtual field trips is flexibility; the same resource can be used for a range of purposes. For example, a virtual field trip to a glaciated landscape could be used for a simple landform identification activity, designed for those new to the topic. However, the same virtual field trip could also provide the basis for a more sophisticated exercise in geomorphological mapping and glacier reconstruction.

A SELF-GUIDED virtual field trip contains little or no embedded information. It requires external inputs (e.g., worksheets, lectures) to transform it into an educational resource.

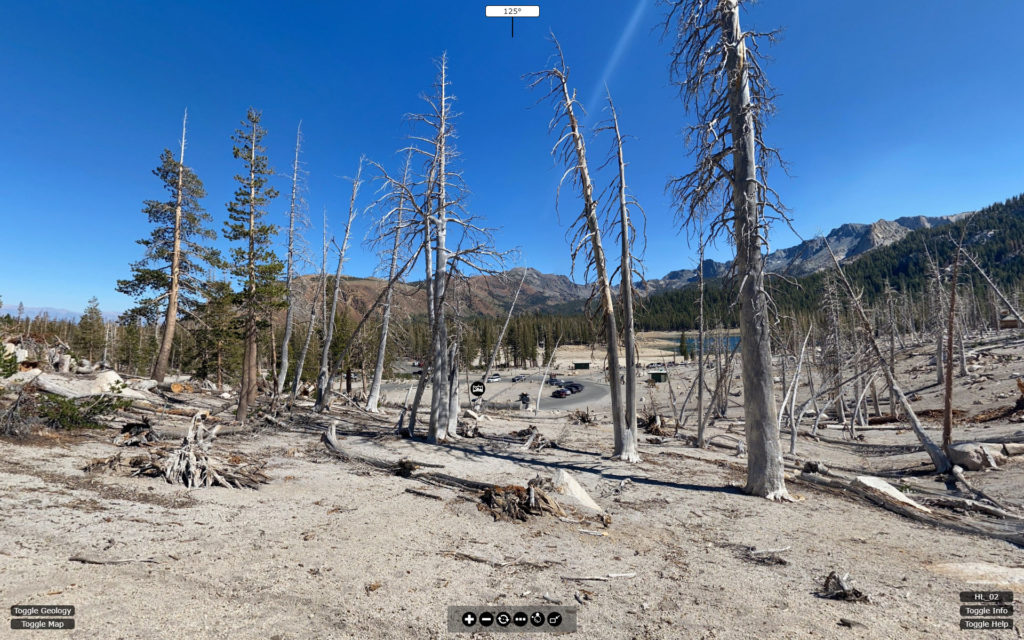

This self-guided virtual field trip is one of many provided for free by Stanford Earth Sciences (who refer to them as virtual field sites). The absence of embedded academic content means it can be used flexibly for a range of academic purposes – assuming the instructor knows enough about the area. If not, the striking image of dead trees and the maps provided would still allow more advanced students to undertake some research to see what is going on here.

The Col du Sanetsch virtual field trip is one of a number provided on the VR Glaciers and Glaciated Landscapes site, hosted by Geography at the University of Worcester. All the virtual field trips to date are self-guided. Worksheets have been developed for a few of them (contact Des McDougall for access).

There are clearly pros and cons to both guided and self-guided approaches.

Guided virtual field trips work well as standalone resources, which may be particularly helpful for outreach activities. Compared to the self-guided approach, however, they are potentially much more time-consuming to develop and less flexible educationally because they are created for a specific purpose.

As to whether guided or self-guided is the right choice for you really depends on what you are trying to achieve. We return to this elsewhere on this site, where we also review other considerations – such as the equipment, software, and time involved.

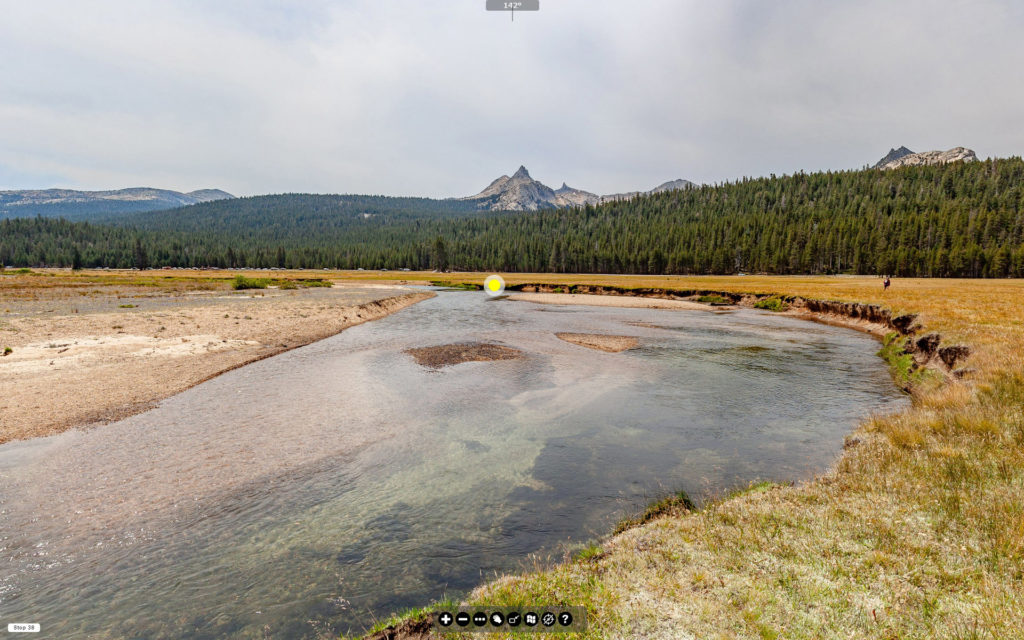

This self-guided virtual field trip to Tuolumne Meadows in the Sierra Nevada (California) was developed as a joint collaboration between UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences and Geography at the University of Worcester. The ‘More Inclusive Fieldwork’ project aims to foster informal collaborations for resource development.

Bringing it together

We can therefore describe (or classify) virtual field trips as follows:

guided or self-guided

and

immersive or non-immersive

For example, the VR Glaciers and Glaciated Landscapes virtual field trips can be described as self-guided, immersive virtual field trips using this approach.

Unfortunately, the pedagogic literature is replete with terminological confusion when it comes to virtual field trip classification, so it is important to note that different authors may employ these terms in different ways – and, indeed, may use different terms altogether to describe the same properties. There have been several attempts in the literature to promote a consistent approach to terminology, but none has gained traction. As it stands, the current approach is neither more nor less valid than others that have been proposed.

Virtual fieldwork and virtual reality

We use the terms ‘virtual fieldwork’ and ‘virtual reality’ interchangeably, but only where the former comprises immersive imagery. Thus, we would describe the virtual field trips in VR Glaciers and Glaciated Landscapes as being examples of ‘virtual reality’ because they place the viewer in the field and provide some autonomy. These virtual field trips can also be viewed with some VR headsets.

It is tempting to think that virtual reality resources need to be viewed with VR Headsets (also known as Head-Mounted Displays – HMDs). This is not the case. They do have some value, but they are not comfortable to use for prolonged periods. There are other issues, including display quality. These issues will be resolved in time. In the meantime, it seems likely that the majority of educational VR content will be consumed on standard computers and mobile devices.

Immersive virtual field trips can also be developed using games engines (e.g., Unreal, Unity 3D). These provide more opportunities for interactivity, and they are the only approach allowing users to navigate true 3D space. The current absence of visual realism in virtual field trips created using games engines is a pragmatic trade-off rather than a technology limitation; replicating a fully realistic world is possible, but expensive for both the developer and the user (in terms of computing power and data download) unless the area is small. For these reasons, we focus on more accessible photography-based approaches to virtual fieldwork development.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.